The Last Laugh / The Last Man

The Last Laugh / The Last Man

Germany 1924, 88 min. | HD-s/w-restored version

The Last Laugh / The Last Man gets by almost entirely without intertitles and is thus the first silent film in which this was successfully implemented. This is due on the one hand to Emil Jannings' impressive performance, but also to the technical virtuosity of the film: Karl Freund's camera moves "unleashed" through the rooms and visualises, also through the combination of dream sequences, dissolves and special effects, the soul life of its protagonist. Such a strong subjectification of the camera's gaze had never been seen before in German silent film.

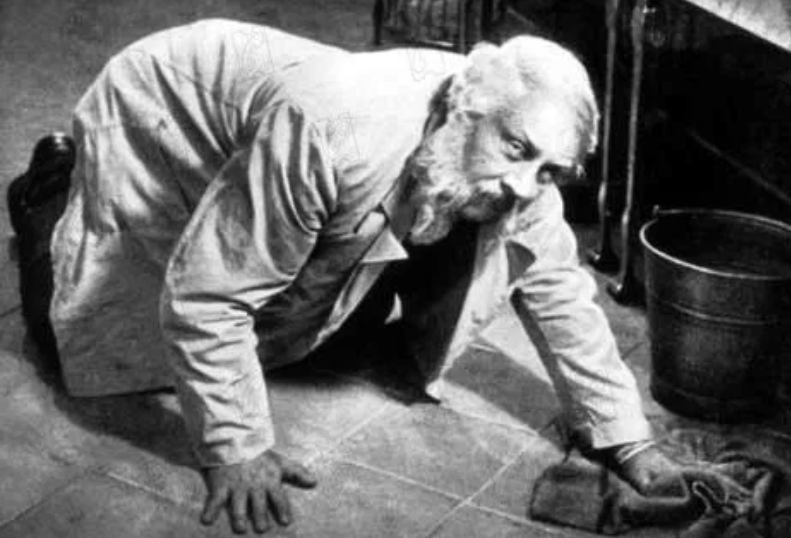

Berlin, early 20th century. The old porter of the hotel "Atlantic" owes his self-esteem and recognition to his splendid uniform: in front of the revolving door of the hotel he is the proud servant who greets the guests, at home in the backyard milieu he is a much admired man. But one day the manager observes how difficult it is for the old porter to handle the suitcases: he banishes him to the cellar and demotes him to toilet man. In his milieu, he does not dare to admit his relegation. When his daughter marries, he steals the uniform to at least keep up appearances. But the swindle is discovered, he is ridiculed and humiliated by his housemates, his relatives turn their backs on him. In despair, the old man retreats to the washroom of the hotel toilet.

F. W. Murnau has attached to this plot, separated by the film's only intertitle, a bitterly ironic happy ending forced upon him: In the toilet, a rich hotel guest dies in the arms of the old man and bequeaths him his entire fortune. Thus the "last man" becomes a courted hotel guest.

Giuseppe Becca's music is one of the few surviving film scores of the silent era. It has survived as a piano direction and violin part. Acts 2, 4 and 5 are notated throughout; in Acts 1 and 3 there are references to pieces by other composers in addition to written-out passages; for Act 6 Becce recommends only five shimmies.

The passages written out by Becce are interesting; as Detlev Glanert writes, "...Becce has endeavoured to compose a continuous composition, which is the real rediscovery for us; Acts 2 to 5 are composed through to 5 minutes, with quite deliberately set leitmotifs, leitmotifs and leitklangs. Acts 2, 4 and 5 in particular feature motifs and melodic sections of great potency that either seem to await further musical development, or sound like a commentary on something not yet performed before. The conciseness of these passages is surprising; in his best moments Becce achieves a cuddliness in the music that is completely equal to the film, its motifs and interjections circling the visual events in an unforced and intelligent way." What remains transparent in the newly created pastiche composition is Becce's typical compilation technique, in that Detlev Glanert plays with the existing quotations (e.g. the Wedding March). Based on this stock of themes and functional connections, Detlev Glanert has made an arrangement with which - after almost 80 years - he attempts to realise and complete what Becce had in mind as individual, expressive incidental music to this classic of German silent film.

The Last Laugh / The Last Man

Film Music for Orchestra by Giuseppe Becce / Detlev Glanert (Reconstruction and Arrangement (2002)

Instrumentation:

1+1/pic.1+1/ca.2.1+1/cbsn – 2.2.1.0 – timp.2perc – pno/ hrm – strings (6.5.4.3.2)

Luciano Berriatúa, who restored the film on behalf of the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, discovered in the course of his work that three original negatives of THE LAST MAN originally existed: one negative for Germany, one for general export and a third for the USA.

The American version (The Last Laugh) has survived almost entirely in a nitrate print that was pulled for distribution in Australia by a New York company in the mid-1920s and has now been found in Canberra.

The source material for the restoration of the German version and the export version was the camera negative preserved in the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv Berlin, as well as a historical nitrate copy from the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Both materials no longer correspond to the original montage of the film, as Ufa had made changes to the German negative and the export negative in 1936 and mixed the two versions. However, both materials complement each other and thus represented an optimal source material for the restoration. In addition, shots from a copy of the Cinémathèque Suisse were used. Essentially, these are the intertitles or shots containing German texts in the picture.

With these materials, the two original negatives, intended for Germany and for export, could be identified and reconstructed in their original cutting order; the various shot numberings (scratched or with ink on the perforation edge) proved very helpful. Since nitrate materials from the original negative or first-generation copies were available for the restoration, the three negatives and cut versions are now available again in the best possible image quality.

The composer Giuseppe Becce

Born in Upper Italy in 1877, Becce came to Berlin around 1900 as a geography student, studied music there and made his debut as a composer of operas and operettas in 1910. His first spectacular contact with film came through the film producer Oskar Messter: Becce played Richard Wagner in the eponymous Messter production in 1913 and composed the film music in his style, which in turn saved Messter from paying high licences to the Wagner heirs.

From then on, Becce's unique career as a film musician and music theorist begins. He arranges countless illustration scores, writes songs and motifs and works as a conductor at the leading premiere cinemas in Berlin: from 1915 to 1923 he conducts the orchestra in the Mozart Hall for the Messter film production, in 1922 he takes over the orchestra of the Ufa Pavilion at Nollendorfplatz, from 1923 he additionally conducts at the Tauentzien-Palast and from 1926 at the Gloria-Palast. A number of Becce's original compositions have survived from the silent film era; his most important ones, apart from the Richard Wagner music already mentioned, are the compositions for the two Murnau films Der letzte Mann (The Last Man, 1924) and Tartüff (Tartuffe, 1925). He also went down in the history of film music because of his 'Kinotheken': Collections of Music Pieces for Use in the Cinema (Piano or Orchestra), which appeared from 1918 onwards. In 1927, together with Hans Erdmann, he published the two-volume 'Allgemeine Handbuch der Filmmusik' (General Handbook of Film Music), a collection of about 3000 pieces of music suggested for the accompaniment of film situations described in key words.

Becce successfully tested himself in various film genres, composing over 100 film scores until his old age; the mountain films he set to music were particularly popular, such as Das Blaue Licht (1931, Leni Riefenstahl), the sound film version of Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü (1935, Arnold Fanck), as well as Berge in Flammen (1931) and Der Feuerteufel (1939/40) by Luis Trenker, with whom he also worked a great deal after the Second World War. He worked together with him a lot after the Second World War. From then on, until the end of the 50's, he almost only did soundtracks for homeland and documentary mountain films. Becce died in 1973 in Berlin at the age of 96.

Born 1960 in Hamburg. 1981-1988 studied composition with Diether de la Motte, Günter Friedrichs and Frank Michael Beyer, including four years with Hans Werner Henze in Cologne. 1989-1993 permanent member of the Cantiere Internazionale D'Arte in Montepulciano (Italy), 1993 scholarship holder at the German Academy Villa Massimo in Rome. 1993 Rolf Liebermann Opera Prize for Der Spiegel des großen Kaisers. 2001 Bavarian Opera Prize for the premiere of the opera Scherz, Satire, Ironie und tiefere Bedeutung in Halle.

Since then Detlev Glanert has pursued a remarkable career as an opera and concert composer and is one of the most frequently performed living opera composers in Germany. His opera, orchestral and chamber music reveals a flair for a particularly lyrical musical language and a connection with tradition that is illuminated anew from a contemporary perspective. In the 2020/21 season alone, three new opera productions are on the repertoire in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, as well as two world premieres in Glasgow and Prague. Glanert's works have recently been performed by the Vienna Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the Berlin and Munich Philharmonic Orchestras, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Czech Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestra del Teatro Regio, the Orchestre National de France, the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, the NDR Radiophilharmonie and the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne.

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau is probably the most important German film director of the silent era, a visionary of cinema. Murnau first worked in Marx Reinhardt's theatre. In 1919 he directed his first film, The Boy in Blue, and established himself as a prolific director. Until 1922, the year of the premiere of Nosferatu - A Symphony of Horror, Murnau made ten films in only three years, seven of which are lost or have only survived as fragments. Then followed the films that still make up the radiance of Weimar cinema today: Phantom (1922), The Grand Duke's Finances (1924), The Last Man (1924), Tartüff (1925) and Faust (1926). From 1927 he worked in the USA. There he made Sunrise (1927), Four Devils (1928, lost) and City Girl (1930). In the same year he made Tabu, the premiere of which Murnau did not live to see.

Credits

- Direction:

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau - Screenplay:

Carl Meyer - Camera:

Karl Freund - Actors:

Emil Jannings (hotel porter), Maly Delschaft (niece of the hotel porter), Max Hiller (niece's groom), Emilie Kurz (groom's aunt), Hans Unterkircher (managing director of the hotel), Olaf Storm (young guest), Hermann Vallentin (pot-bellied guest) Georg John (night guard), Emmy Wyda (skinny neighbour) a.m. - Film restoration (2002):

Luciano Berriatúa, commissioned by Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Foundation - Score music (2002):

Giuseppe Becce/Detlev Glanert (reconstruction commissioned by ZDF in collaboration with Arte) - Editorial:

Nina Goslar, ZDF - Production:

Thomas Schmölz, 2eleven music film